Great Britain

Aircraft evolve rapidly after the Wright brother’s flights, aided by the parallel development of the internal combustion engine. By the late 1920’s unprecedented speeds and heights have been reached. Many are dazzled by this progress. A few wonder if it can be maintained without a drastic evolution in technology

In 1920 the UK Air Ministry request a confidential report on the feasibility of the gas turbine as a means to drive an aircraft propeller. The conclusion is that such an engine would be too large, heavy and inefficient. However, in 1926, a report by Dr A.A.Griffith at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) casts a more optimistic light on the matter. The authorities are persuaded that research into axial compressor design should be undertaken. Work is therefore begun under Griffith in 1927, but then ceases in 1930 when funding is withdrawn due to disappointing progress.

Great Britain

Great Britain

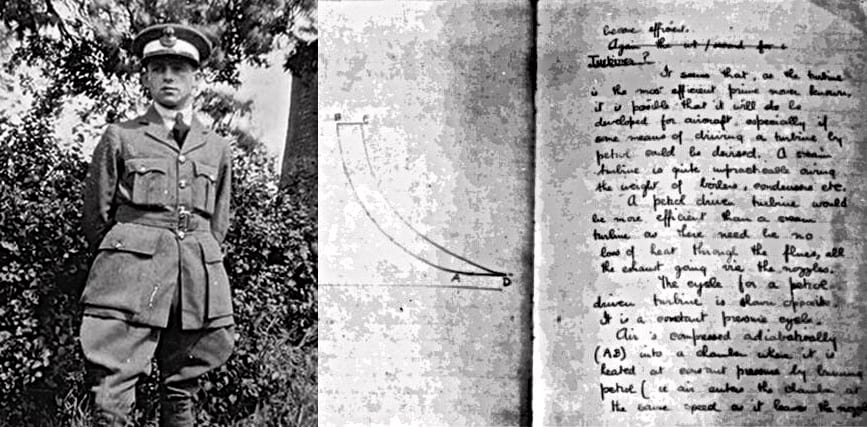

Frank Whittle, a Royal Air Force officer cadet, writes a thesis demonstrating by calculation the potential of the gas turbine for aero-propulsion at high speeds and altitudes

This was written during the first half of 1928, the second year of his cadetship. At the time the maximum speed of RAF fighters was 160mph and the service ceiling was about 27,000ft. Whittle was thinking in terms of 500mph and 40,000ft.Great Britain

Great Britain

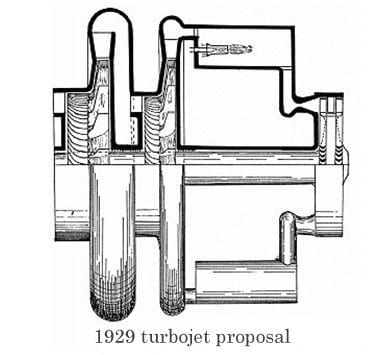

October 1929: Now an officer, Whittle conceives that the most effective way to exploit the potential of the gas turbine is as a turbojet rather than as a means to drive a propeller

The Air Ministry asks Dr Griffith to assess Whittle’s proposal. For reasons never satisfactorily explained, he advises that the idea is without merit and not worthy of further research.Great Britain

Great Britain

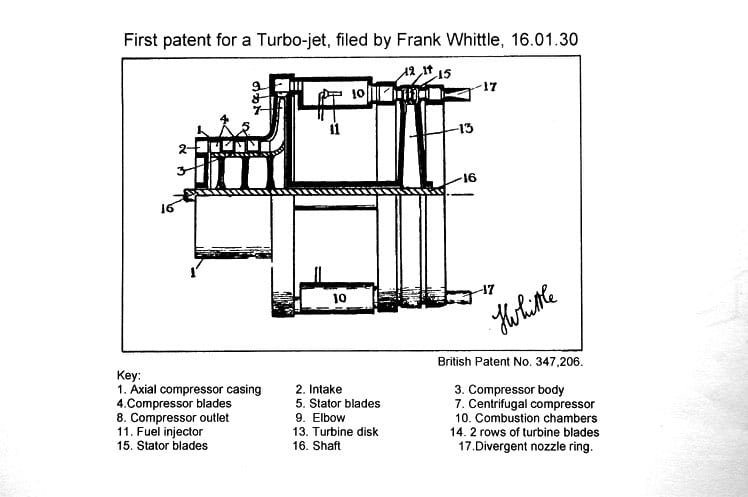

January 1930: Whittle applies for a provisional patent

Whittle considers that a compression ratio of 4:1 can be achieved with a 2-stage centrifugal compressor. However, for patent purposes, an axial stage is included in the application. The Air Ministry takes no constructive interest. Gas turbine research at the RAE is discontinued.Great Britain

Great Britain

April 1931: Whittle’s full patent is granted. The Air Ministry fail to render it secret and it enters the public domain

August 1931: The patent is registered at the Berlin Patent Office. Subsequently the details appear in a German technical journal that is circulated to aeronautical industries and research establishments – including the Aerodynamic Research Division (AVA) at Gottingen.

Great Britain

Great Britain

January 1934: Due to a lack of funds for the renewal fee and a lack of support from the Air Ministry, Whittle allows his patent to lapse

However, recognising Whittle’s engineering ability, the RAF send him to Cambridge University to study mechanical sciences.

In Sweden, Alf Lysholm proposes his version of a turbojet.

Great Britain

Great Britain

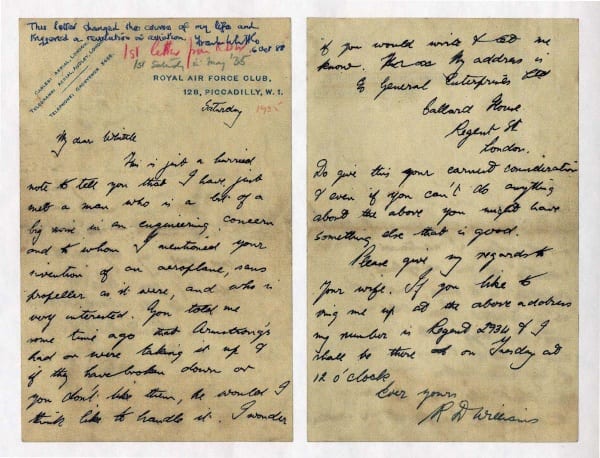

May 1935: “This letter changed the course of my life and triggered a revolution in aviation.”

The letter from his friend R.D.Williams, received by Whittle when he was halfway through his engineering course, expressed keen interest in the turbojet idea. It was crucial in re-awakening Whittle’s enthusiasm and led directly to the creation of Power Jets Ltd. As a result, the turbojet was effectively rescued from oblivion in Great Britain.Great Britain

Germany

1936: In Germany, Hans von Ohain takes his centrifugal-compressor turbojet proposal to the Heinkel Aircraft Company – secret development begins

Coincidentally, at the Junkers Aircraft Company, Herbert Wagner secretly begins development of a promising form of axial turbojet. In Britain, following his graduation, the RAF permits Whittle to to work on his turbojet project – initially as Post Graduate Studies and then by posting him onto the Special Duties List. As a direct consequence, the Air Ministry are galvanised into resurrecting aero gas-turbine research at the RAE. However, Griffith’s influence prevails and work is focussed on a gas turbine designed to produce shaft horsepower to drive the aeroplane propeller.Germany

Great Britain

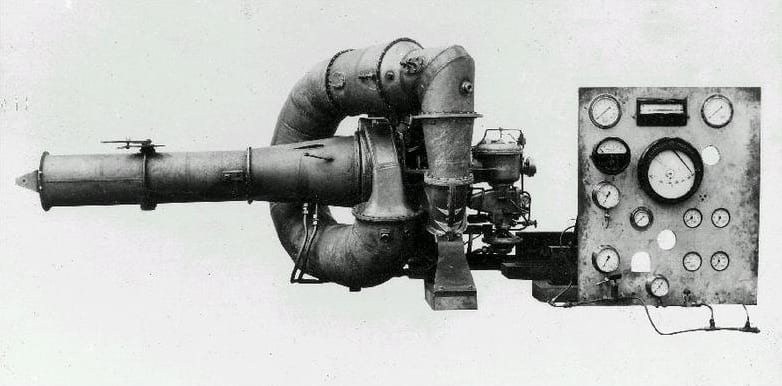

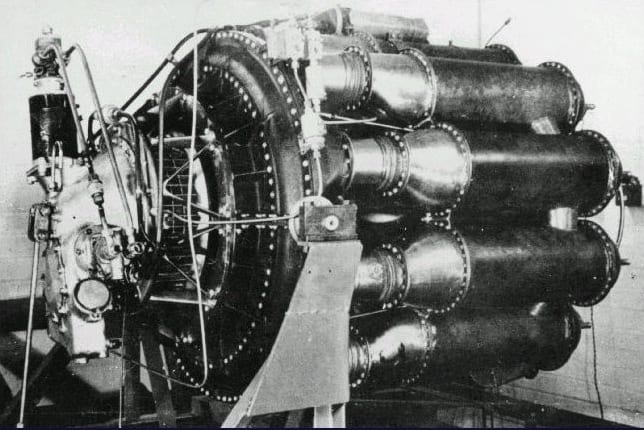

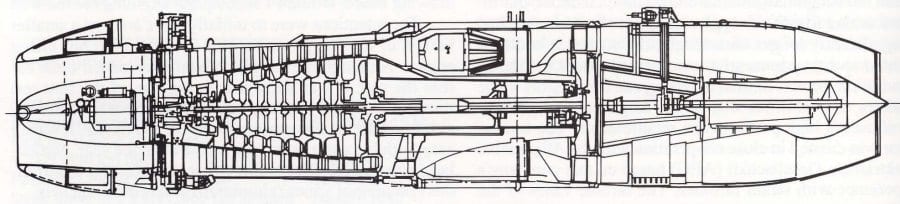

April 1937: Whittle successfully runs the first turbojet engine – the WU

This initial form of the engine has a double-sided centrifugal compressor, a single combustion chamber and a single-stage axial turbine. Initially tests are at the British Thompson Houston Company at Rugby but subsequently move to a disused foundry in Lutterworth. Becoming aware that the engine has potential but that the venture is in a parlous financial state, the Air Ministry gives some support by paying for test results.Great Britain

Germany

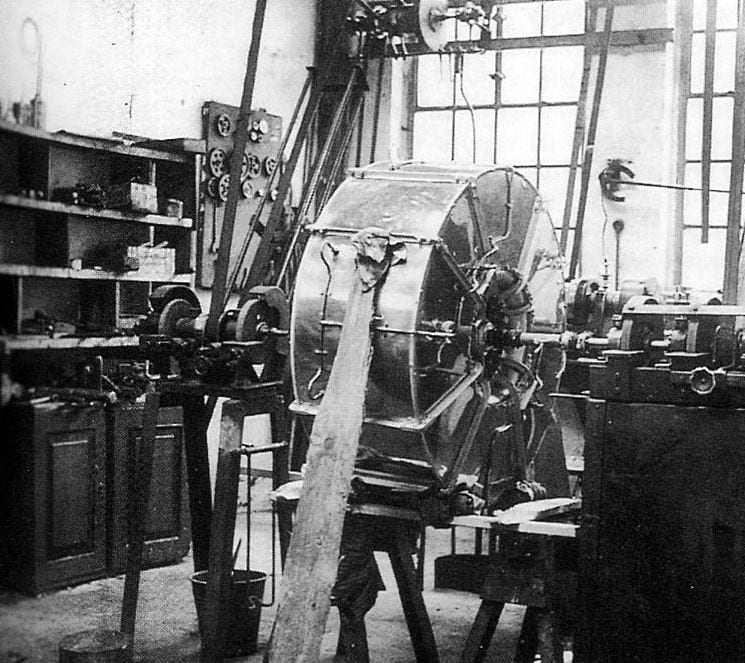

September 1937: A pressed-steel version of Ohain’s engine is run

According to Ernst Heinkel in his memoir “Sturmisches Leben” (Stormy Life), Ohain first runs this version on gaseous hydrogen in September. Approximately 6 months later, a more realistic version is run on gasolene – this is designated He.S3A.The Ohain rotor undergoing an externally-driven dry run to test airflow characteristics, earlier in 1937.

Germany

Germany

1938: The German Air Ministry (RLM) call upon aero-engine manufacturers to take-up turbojet development

German enthusiasm for the turbojet is evidenced when the RLM, led by Helmut Schelp and Hans Mauch, call for research and development of turbojet technology exclusively from aero-engine manufacturers. They indicate that support will only be given for axial-compressor projects. They also call upon airframe manufacturers to design a twin-engine jet fighter to be capable of 800kph / Mach 0.82 and an endurance of one hour. The Wagner engine, suffering from compressor problems,fails to run successfully.Germany

Great Britain

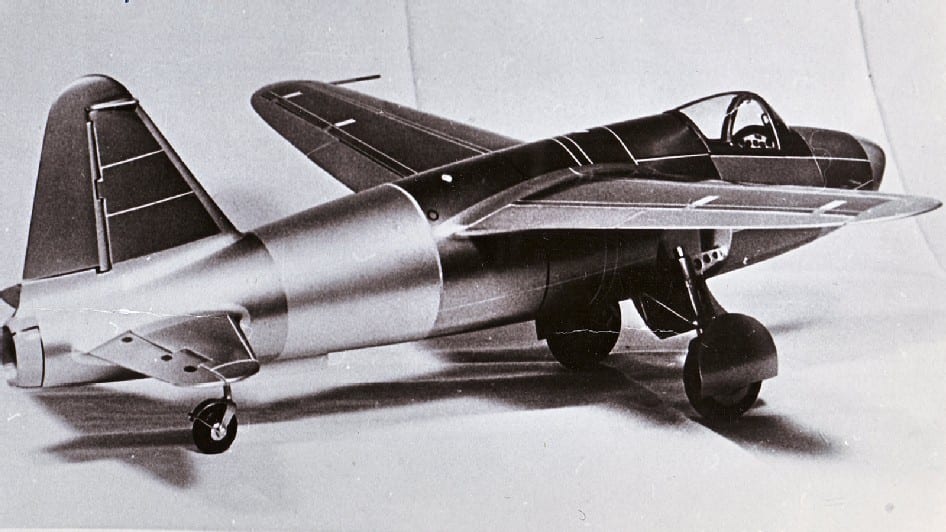

June 1939: In Britain, the Director of Scientific Research witnesses the WU under test and orders a flight-worthy engine, the W1. The Gloster Aircraft Co. are contracted to design and build an airframe – the E28/39

The aircraft is designed to explore the full potential of the W1 and later marques of the engine. The RAE convert their project to an axial turbojet. This eventually becomes the MetroVic F2 – the only British axial-compressor engine under development during the war. Griffiths resigns and moves to Rolls-Royce, where his highly complex turboprop engine is eventually adandoned in 1944.

Great Britain

Germany

August 1939: The world’s first turbojet flight

Powered by the short-lived Ohain engine, the Heinkel He. 178 makes a 6 minute flight in August and again in November. By demonstrating his involvement, Heinkel hopes to gain official support despite the fact that he is an airframe manufacturer and that the Ohain engine has a centrifugal compressor. However the flight demonstration fails to impress the RLM. The now promising Wagner project migrates to Heinkel under an ex-Junkers team of engineers.Germany

Great Britain

March 1940: British Air Ministry places contracts for W2B engines to be built primarily by Rover to power a twin-engine fighter, the Gloster “Meteor”

This is to be in collaboration with Power Jets. However, partly to accumulate intellectual property, Rover embarks on secretive and time-consuming design changes. In June ’41, collaborating fully with Power Jets, de Havilland begin their own design for a centrifugal tubojet under Major Halford.Great Britain

Germany

April 1941: With a highly modified form of the Ohain engine (He.S8) Heinkel’s He.280 prototype twin-engine fighter is demonstrated before the Nazi hierarchy

Heinkel had originally tailored the He.280 to take the He.S30 axial-compressor engine, based on Herbert Wagner’s design. Development problems lead to delays, and a much-modified version of the Ohain engine is installed as an expedient. However, the RLM give preference to the Me.262 and focus their support on Junkers and BMW engine designs, both of which are based on axial compressors. Subsequently, further development of the Ohain engine is abandoned.Germany

Great Britain

May 1941: First flight of the E28/39 powered by the W1 – flight duration 17 minutes

A few days after the first flight, with thrust set at 1000lbs, the E28/39 reaches a speed of 370mph at 25,000ft – exceeding the performance of contemporary fighters. Meanwhile development of the W2B is delayed by surge problems and Rover’s design alterations – especially the introduction of straight-through combustion with a necessarily extended rotor-shaft.Great Britain

United States

October 1941:The USA enters the jet age

The head of the US Army Air Corps, General Arnold, had been made aware of progress with jet propulsion in Britain and had requested that the USA should be given the opportunity to take up the technology. Accordingly, in October 1941, a W1 engine and plans for the W2 are delivered to General Electric for development to begin under licence.

United States

Germany

Parallel to the development of the Junkers Jumo 004 A-O, Hermann Oestrich at BMW has designed the similar BMW-003 axial engine – the compressors of both were designed by Walter Encke at Gottingen. However, the RLM favour the 004 due to its greater manufacturing simplicity. Even at the end of the war, these engines continue to suffer serious problems relating to compressor surge and have a very short time between overhaul and a total life of around 25 hours.

Germany

Great Britain

March 1942: Design of W2/500 commenced. It runs 6 months later and performs exactly as predicted – with no handling problems

Great Britain

United States

Oct 1942: Powered by the GE-built Whittle engine, the first US jet-propelled aircraft, the Bell P-59 Airacomet, begins flight-trials

United States

Great Britain

April 1943: Rolls Royce take over the W2B from Rover, solving many of the technical and political delays hindering its development and putting it into production as the Welland

Delays to the W2B had led to the Meteor’s first flight being powered by the de Havilland H1 in March. The first flight using the W2B engine takes place in July and this engine (Welland) powers the Meteor when it becomes operational the following year.Great Britain

Great Britain

In late July 1944, the Gloster Meteor twin-engine jet fighter, powered by the W2B, enters RAF service with 616 Squadron – deployed against the German V1 Flying Bomb

Great Britain

Germany

October 1944: The Me.262 twin-engine jet fighter, powered by the Jumo 004B engine, becomes operational with the Luftwaffe and is deployed against Allied bomber forces

The Me.262 first flies with Jumo 004 A-0 engines in July 1942 and with the 004B-0 engines in March 1943. By October 1943 flight trials using the 004 B-1 production engine have begun. It is not until September that sufficient engines come off the supply chain to render the Me.262 and (later) the Arado 234 (reconnaissance bomber) operational. More aerodynamically sophisticated than the Meteor and with a significantly higher wing loading it achieves 830kph/520mph with engines of similar thrust.Germany

May 1945: By the end of the war in Europe, the superiority of the turbojet for high-performance aircraft is proven

The next generation of fighters are powered by developments of the centrifugal compressor engines – the Rolls-Royce Nene, de Havilland Ghost and General Electric J33/J35 of 3,550 – 5,000lbs thrust and all tracing their origins to Power Jets designs. With the Cold War looming and a civil market re-opening, there is now a scramble by countries and their aero-engine manufacturers to acquire and invest in this new technology. German experience is quickly disseminated and absorbed, whilst Russia becomes a major player in the East when the British government allows Derwent and Nene engines to be supplied to the USSR in 1946.

1946 and beyond. With the surge and stall problems of axial-flow engines gradually overcome, development focuses on higher power and greater fuel efficiency – unlike piston engines, gas turbines now prove to have few technical constraints on size

Rolls-Royce, Armstrong Siddeley (UK) and General Electric(US) develop powerful axial-compressor turbojets, initially of around 7,000lbs thrust but increasing to 10,000lbs, both British engines drawing on Griffith’s axial compressor research. A plan for the first truly supersonic aircraft, the Miles 52, powered by a Whittle W2/700 engine, prompts Whittle to propose an aft-mounted fan (an extension of the turbine blading) with fuel injected into the jet-pipe to create an after-burner. He separately proposes an axial-compressor (front-fan) turofan engine,producing the one of the first application of reheat or afterburning, as well as augmenting this with an engine-driven fan ducting air around the engine – a form of bypass. Both these features will later become common. He separately proposes an axial-compressor (front fan) turbofan engine, the LR1. However the British Government cancels the M 52 in February ’46 and, under pressure from aero-engine manufacturers, also bans Power Jets from designing and developing new forms of turbojets. Disastrously, the revolutionary LR1 turbofan is also cancelled. The first applications of turbojet engines to airliners results in the de Havilland Comet, which enters service in 1952, and the Boeing 707 (in service from 1958). By the end of the century airliners will be powered by turbofan engines developing over 100.000ibs thrust and carrying four times the number of passengers. The development of turbojet engines with steadily higher bypass ratios and increasing efficiency, means that the initially-popular turbo-prop occupies a shrinking market in the short haul sector. Centrifugal-compressor engines, more compact and robust, continue to have applications at lower thrusts, although mainly in specialised applications, such as helicopters.

Sources

The documents and other sources consulted in compiling this timeline include:

- Royal Aircraft Establishment Stern Report 1920.

- Science Museum Archives.

- Churchill College, Cambridge, Archives.

- National Patent Office,UK.

- Berlin Patent Office.

- Herbert Wagner – his life and work, Deutches Museum.

- Flugmotoren und Strahltriebwerke – by von Gersdorff, Grasman and Schubert.

- Sturmisches Leben – by Ernst Heinkel.

- Aeronautical Research in Germany – by Hirs, Prem and Madelung.

- History of German Aviation – by Anthony Kay.

- German Jet Engines – by Anthony Kay.

- Whittle, the True Story – by John Golley

- Jet – by Frank Whittle.

- The Jet Pioneers – by Glyn Jones.

- Jet Pioneers – by Tim Kershaw.

- Jet and Turbine Aero Engines – by Bill Gunston.

- Development of Aircraft Engines – by Robert Schlaifer.

- Elegance in Flight – by Margaret Conner.

- Plane Sailing – by Bill Gunston.

- Gloster Meteor – by Phil Butler and Tony Buttler.

- Miles M52 – by Capt. Eric Brown.